What’s Next, and What’s After That: Navigating Through Hyperchange

In a time of cascading disruptions, leaders need to look beyond immediate risks to also focus on the second and third order effects shaping their world. This piece draws on the kinds of business strategy and foresight tools, adapting them to the social sector, to help organizations anticipate change and respond early. The takeaway: building strategic foresight into everyday planning is key to staying mission driven and ready for what’s next.

A 2009 piece for The McKinsey Quarterly entitled “Risk: Seeing Around the Corners,” by Eric Lamarre and Martin Pergler, shone a light on the importance of leaders considering not only the direct risks that organizations face from disruptions in their operating environment. They urged also looking at the second and third order consequences of those disruptions. Sometimes those cascading consequences have greater impact than the initial direct event or upheaval.

Think of a social version of the butterfly effect, a phenomenon postulated by meteorologist Edward Lorenz, in which the formation and path of a tornado in Texas is influenced by a butterfly flapping its wings several weeks earlier in Brazil.

That butterfly effect is how many organizational leaders feel about life in today’s environment. It’s a time we might describe as one of hyper-change, where disruptions are happening in multiple dimensions simultaneously, and their effects are colliding with one another in an ever-accelerating way. Every one of those collisions sets in motion a cascade of direct as well as second- and third-order consequences. Some are obvious, and some we won’t see coming – unless we’re sensitized, and trained, to anticipate them.

Image credit: davidstarlyte.com, beliefnet.com

More and more, changes ripple through multiple dimensions

Think about what we’ve been experiencing just over the last five years, and the downstream effects we’ve seen and are still seeing today from those disruptions. Some may feel the COVID pandemic is in the rearview mirror, but its impacts continue to flow down onto how we work, on social equity, on educational attainment, and more. Add to that how automation and AI are racing forward; how trade tensions are impacting supply chains and economic growth; how climate change is driving migration patterns, food insecurity, degradation of critical infrastructure, and more. In each of these areas, we’re seeing the direct impacts, and also a growing number of secondary and tertiary impacts, all playing out simultaneously. News analyses look at what it all means at a macro level. Leaders need to look at what it means specifically for their organizations.

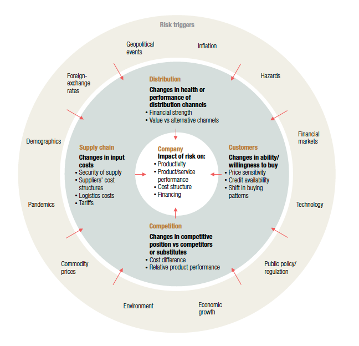

In their McKinsey article, Lamarre and Pergler focus on commercial businesses, and the risks businesses face from cascading consequences of disruptions in a single dimension (the economy).

Nonprofit and other social impact sector organizations certainly need to worry about the indirect consequences for them of economic factors like currency appreciations and depreciations, spikes or drops in oil prices, inflationary pressures on households’ spending, and the like. And like businesses they’re also vulnerable, directly and indirectly, to disruptions in the social, political, technological, and other spheres. That demands that they play a multi-level chess game of risk anticipation and proactive risk management, with the success of the enterprise mission at stake.

The McKinsey piece offers a framework useful for nonprofit leaders to adapt for their purposes. Without naming it, it also makes a nod to tools from strategic foresight that can help nonprofit leaders think their way through what could affect them at the second and third orders of consequences from such disruptions. Let’s dig into both.

Rattling the value network

First the framework. Looking at four key elements of what we might call the value network or market ecosystem – competitors, supply chains, distribution channels, and competitors – helps illustrate how second- and third-order ripples of a disruption in the economy can impact the commercial success, and even the viability, of a business. For example:

How might that business be affected as the economy-wide shift to remote work not only blows up longstanding operating processes (direct risk), but then goes on to boost the ability of competitors who had already invested in remote work infrastructure to attract top talent (second order effect)?

Or what if geopolitically motivated trade restrictions make some of the company’s critical production inputs hard to access (direct risk), and then those losses in turn spur institutional investors to shift capital to companies with diversified supply chains (second order effect)?

What if those same trade restrictions lead to other, different second order effects – like delayed or missed deliveries by distribution channels the company is highly dependent on, damaging not only the distributor's reputation but also the company’s?

What if an economic downturn raises the cost of basic necessities and thereby increases price sensitivity in the company’s customer base, and the resultant revenue and profit losses then force the company to reduce its investment in R&D and innovation?

Image: Lamarre + Pergler, McKinsey Quarterly

For mission-driven organizations it’s the same, just different

Nonprofits may not intuitively think of these in the same way as a business does, but these elements of the value network certainly are there. Instead of competing and deal-making to generate shareholder value, nonprofits create social value through a network of mission-aligned activities, with different stakeholders playing analogous roles to those in the private sector. For example:

Competitors: you may think of them more as “peers,” but other nonprofits, social enterprises, and even governments serve the same communities you do, offer similar services (e.g., education, access to healthcare, help finding jobs), and jockey for the same funding.

What could some of the second-order consequences be for your nonprofit in this part of the value chain, for example from a sudden shift in government policy like a cutoff of funding? One or more of those organizations could pivot to a new operating model; several could band together in a merger. At the next order of consequence from there, what could result from those moves?

Supply Chain: nonprofits rely on goods like businesses do, which they can lose timely or affordable access to when economic conditions change. They also rely on a “mission supply chain” of knowledge providers, technical experts, local implementation partners; even donor funding tranches, all of which can be seen as part of a nonprofit’s mission supply chain.

What could some of the second-order consequences be for your nonprofit in this part of the value chain, for example as AI changes labor market dynamics? Some of those experts and partners could be enticed away from the social sector; more positively, all their combined knowledge could become available to you in bots at a fraction of the cost. At the next order of consequence, what could result if those prospects came to be?

Distribution Channels: there’s a growing variety of ways in which nonprofits reach their users and scale their impact: direct delivery (field teams, clinics, shelters); partner networks (local NGOs, local governments, faith-based groups); digital platforms (apps, SMS campaigns, telehealth); policy channels (advocacy, legal actions).

What could some of the second-order consequences be for your nonprofit in this part of the value chain, for example if areas you serve become inaccessible due to an outbreak of conflict, or from a climate change-induced environmental disaster? Telecommunications failures could create new vulnerabilities for communities, demanding new kinds of relief services you may or may not be able to provide; misinformation could diminish trust in institutions. At the next order of consequence, what could result if those prospects came to be?

Customers: even if they don’t use the term “customer,” nonprofit leaders and staff naturally see the beneficiaries of their organization’s services or advocacy as communities whose needs, preferences, perhaps even “loyalty” they need to take into account. And at the same time, the donors, foundations, governments, and impact investors who "pay" for the nonprofit’s value to be created are customers as well.

What could some of the second-order consequences be for your nonprofit in this part of the value chain, for example if political conditions change how foreign entities in a country are perceived, or new for-profit entities emerge with attractive market-based options? Budgets for mission services could become squeezed in favor of investment in security or new kinds of communications campaigns; funders could shift to new causes. At the next order of consequence, what could result if those prospects came to be?

Making sense of it all

Now for the tools. It’s one thing to talk about the importance of thinking proactively through the second- and third-order consequences of disruptions in your operating environment. It’s another thing to understand: how do we do that? The answer lies in two of the cornerstone elements of the discipline of strategic foresight.

Simply put, strategic foresight is a systematic approach many organizations use to collect and consider information about their future operating environment, and to speculate creatively but also with rigor about what it could be like. It’s about anticipating alternative possibilities, and imagining non-linear possible consequences of events external to your organization and beyond its control. And not only what could happen. Crucially, it also enables organizations to foresee what actions they can take to contend with and even get out in front of what could happen.

Two foundational methods of strategic foresight are the key to nonprofits, or any organization, usefully leveraging the framework we’ve adapted above from the McKinsey authors to think through successive impacts of economic, social, political, technological, and other disruptions.

Seeing the disruptions before they disrupt

One is scanning the environment for the trends and disruptions that are already happening in these areas, and for emerging signals of trends that may be just starting to gain momentum. This is where the “what if ...?” prospects come from, like the things we speculated about above (what if a government policy affecting your nonprofit suddenly shifts, what if AI creates new job prospects that attract away key members of your workforce, and so on). Scanning is acquiring data about things that are happening today that portend long-term (and short-term) change. How do you do it? It’s simpler than you may think. The short version is: read widely, and eclectically, and collaboratively.

Image credit: https://sswm.info/

What does that look like? You’re already doing some of it, without realizing it or “naming” it that way. All of us are scanning in what we read in their news feeds and other places day-by-day. You can get great strategic foresight value from that in your nonprofit by putting just a little bit of structure into where and what your people are reading, and encouraging them to stretch to some topic areas and sources they might not ordinarily think or read about. The other key is also putting some structure around the data points and insights your people identify. Capture them in a simple repository of some kind that can benefit the organization as a whole. Then get people together regularly to talk about how all those dots might connect.

Making this a routine part of how your team works together doesn’t have to be a big or burdensome level of effort (and it can be an enjoyable team-building activity). And it pays considerable dividends for “seeing around corners” to the things that could impact your organization directly, and indirectly through how they affect elements of your mission value chain.

Going from “what if” to “if, then ...”

Having found in your scanning some of the important disruptions your organization might encounter, another strategic foresight tool gives you a way to do your next-order thinking about them. It’s called a “futures wheel” or sometimes an “implications wheel.” It’s a structured brainstorming technique to identify and visualize the cascading consequences of each potential disruption. It looks like this:

Image credit: KnowledgeWorks

Take one of our examples from above – a sudden shift in a government policy relevant to your nonprofit or the issue it works on. Make it the “change” at the center of the wheel. One first-order consequence we imagined was competitor organizations shifting to a new operating model that’s favored under the new policy; a second was several of them joining up in a merger. Moving out from there on one spoke of the wheel, your funders could flock to the nonprofits employing the new operating model. On another spoke, branching from the merger at the first order, the new merged entity’s administrative and other efficiencies could make them more adept at serving communities your organization historically has served, inducing them to end their relationship with you. You can go on to identify the next (third) order consequences of losing your funders or your constituents.

Like scanning, going through exercises like this needn’t be a burdensome effort. An afternoon with your team together can generate a “futures wheel” for each of the disruptions you might face. At the end of the day, you’ll have seen around some important corners. You can also gain insight into actions your organization could take to hedge against negative potential consequences, or to take advantage of beneficial outcomes of the disruptions that you’ll also be able to foresee.

Start drawing your navigation chart

The spur for Lamarre and Pergler in 2009 was the then-ongoing Great Financial Crisis (GFC), and how it “reminded us of the valuable lesson that risks gone bad in one part of the economy can set off chain reactions in areas that may seem completely unrelated,” and whose “impacts can be substantial—often, much more substantial than they seem initially.” Today, nonprofits and other organizations face conditions of hyperchange where risks in multiple dimensions of their operating environments can set off chain reactions arguably even more complex than what businesses saw in the GFC.

With the right tools, navigating those changes and risks successfully is possible. Scanning to identify how they could impact the different elements of your mission value chain, and thinking through the successive orders of consequences from those initial potential impacts, is a powerful way to start drawing your navigation chart.